36

DECEMBER 2014

•

WORLD AQUACULTURE

•

WWW.WA S.ORGControlling Inflammation

with Flavanoids—An Option

for Future Aquafeeds

Malte Lohölter, Susanne Kirwan and Bernhard Eckel

W

ith annual growth

rates of approximately 10

percent throughout the last five

decades, the global aquaculture

sector is the fastest growing

food-producing industry in the

world (Pettersson 2010). Despite

great past and present success,

aquaculture is facing diverse

challenges, including a need

for increased productivity and

efficiency while simultaneously

implementing further

replacement of traditional feed

ingredients derived frommarine

fisheries. Achieving these

apparently opposite targets will

be ambitious and likely to have

unexpected side-effects that

need to be taken into account in

expedient diet formulation.

Current research indicates

processes subsumed as

inflammation may be among

these detrimental side-effects,

leading to suboptimal feed

efficiency, animal growth

and eventually affecting

profitability of the production

system. The present article

summarizes current knowledge, providing a glimpse at the potential

future impact of inflammation on cultured aquatic species, while

discussing existing and conceivable solutions.

Impacts of Inflammation

Inflammation is often imprecisely considered a synonym

for infection but should be understood as a complex stereotypic

response of the body to damage of its tissues or undesired chemical

(reactive oxidants, acids, lyes, toxins), physical (foreign objects,

radiation, heat, cold) and biological (viruses, bacteria) stimuli

(Weiss 2008). The main objective of the processes subsumed as

inflammation is to eliminate the damage, stop the spread of injury

and restore the functionality of the affected regions.

The body responds to the onset of inflammation with molecular

changes in gene expression and diverse reactions of the immune

system. In the initial reaction, affected tissues are subjected to an

increased blood flow, followed by altered concentrations of different

plasma proteins and white

blood cells. The liver responds

with increased production of

specific proteins (so-called

acute-phase proteins) that

are capable of destroying

or inhibiting microbes and

subsequently giving a negative

feedback to the inflammatory

response to down-regulate the

physiological response to the

stimuli. At the molecular level,

inflammatory processes are

regulated by a protein complex,

NF-ĸB, which is found in its

inactive form in the liquid

phase of cells. As summarized

in Figure 1, inflammation can

ultimately lead to impaired

liver function, anorexia, pain

and muscle degradation.

But what happens if the

defense mechanisms of the

organism are not able to fully

limit the inflammation to its

transient acute form (lack of

healing)? So-called chronic

inflammation can occur and

lead to the development of

a variety of disorders. In

contrast to acute inflammation, which is typically characterized by

the five signs of pain, heat, redness, swelling and loss of function,

chronic inflammation is often less visible and can affect apparently

healthy animals, which are well supplied with all required nutrients,

according to current recommendations. In humans, chronic

inflammation is known to be related to cancer, allergic reactions,

atherosclerosis and myopathies. As a general consequence of

inflammation, the physiological priority is shifted toward healing

and cell protection, meaning that a considerable amount of dietary

energy and protein is used to control these processes and is no

longer available for tissue and muscle growth. Thus, animals are no

longer able to reach their genetic potential and farmers are likely to

experience economic losses.

The Future Situation

Production losses associated with inflammation are likely to

increase in future aquaculture. Although knowledge and awareness

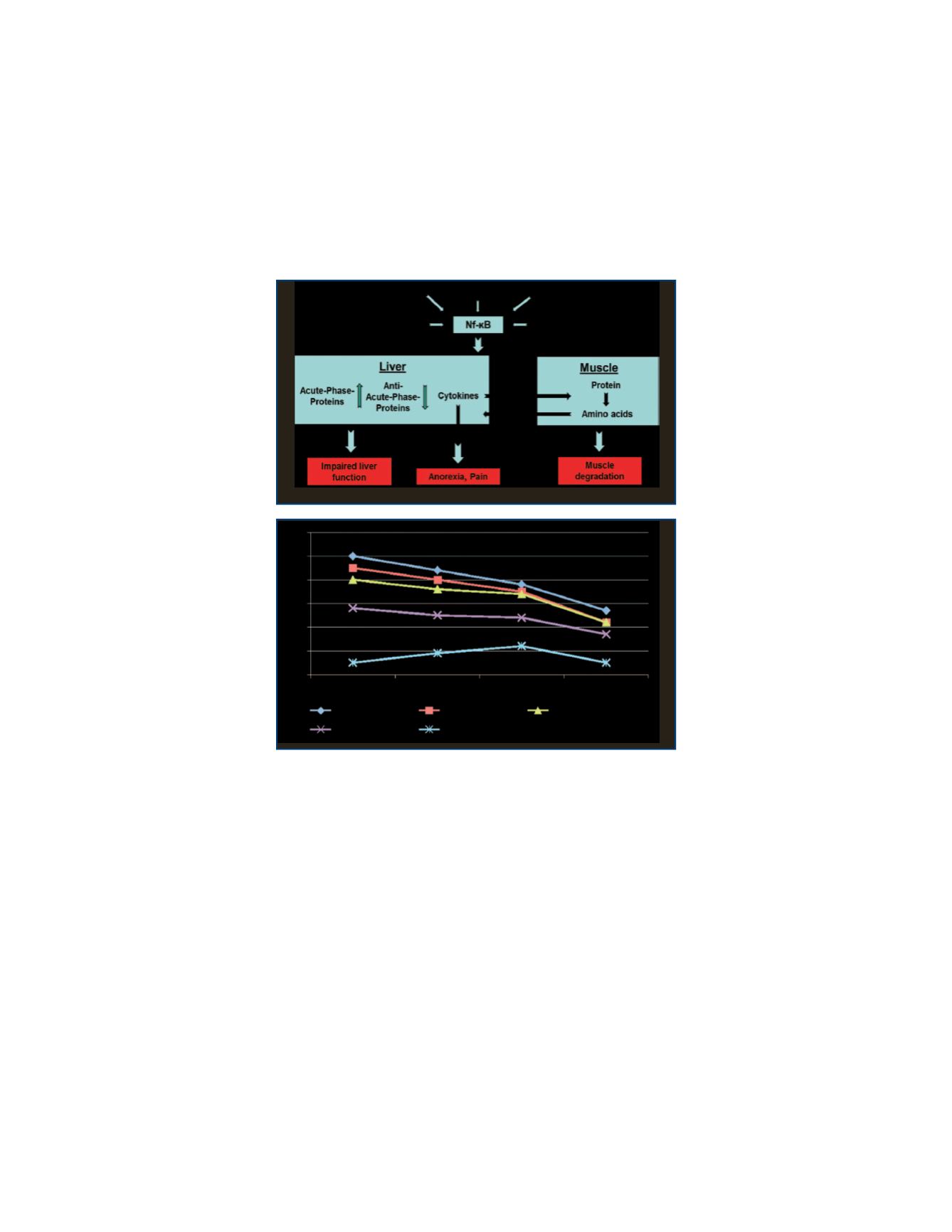

TOP, FIGURE 1.

Physiological effects related to inflammation.

BOTTOM,

FIGURE 2.

Dietary inclusion of fishmeal in aquafeeds from 1995 to 2010 (Redrawn

from Tacon

et al

. 2011).