WWW.WA

S.ORG

WWW.WA

S.ORG

•

WORLD AQUACULTURE

•

DECEMBER 2014

19

(Boaventura

et al

. 1997). Fish on

the downstream part of the river

live in effluent from farms located

upstream.

Water quality is not the only

factor affecting rainbow trout health.

Crowding, improper handling,

grading, pond cleaning and other

routine activities are additional

factors that stress fish and can

lead to increased susceptibility to

pathogens (Pickering 1992). In many

countries, fish farmers are assisted

in the management of water quality

and environmental parameters by

government and academic institutes

and extension agents, but this is not

the case for the trout farmers of

Lebanon.

Aquaculture has generated

massive enthusiasm in the past two

decades, with some viewing its

development as a ‘blue revolution’

with tremendous potential for

food security, economic growth in

rural areas and poverty alleviation.

However, growth in fish farming,

as with all farming activities, has

environmental impacts, which must

be managed if production is to be sustainable.

Other than the flow rate of the Assi River, very little is

known about water quality and no studies of the impact of trout

aquaculture on the Lebanon portion of the stream are available.

Here we describe a study performed on the river to assess levels

of pollution, effects of aquaculture on river water quality and local

stakeholder perceptions of aquaculture and the environment.

Study Survey

A survey of trout farmers along the length of the Assi River in

Lebanon was done in 2012. Farms were identified and a list of 49

farmers who fully or partially own ponds along the Assi River was

established. Geographic coordinates of each farm were estimated

using Google Earth imagery. Survey results cover 199 ponds from

the source of the Assi River to the last accessible point before the

Lebanon-Syria border. Every trout farm owner or manager along

the river was interviewed and informal conversations with the

mayor of Hermel, recreational activity (e.g. rafting and camping)

organizers and restaurant owners bordering the river, were

recorded.

A detailed questionnaire was prepared in English and

translated to Arabic. It included questions related to land and

ponds, fish production, feeding and environmental practices and

the farmers’ personal opinion about the state of aquaculture in the

river valley. Questions were posed at random and in no specific

order. The veracity of some answers was controlled by asking some

farmers if the information given by other farmers was correct.

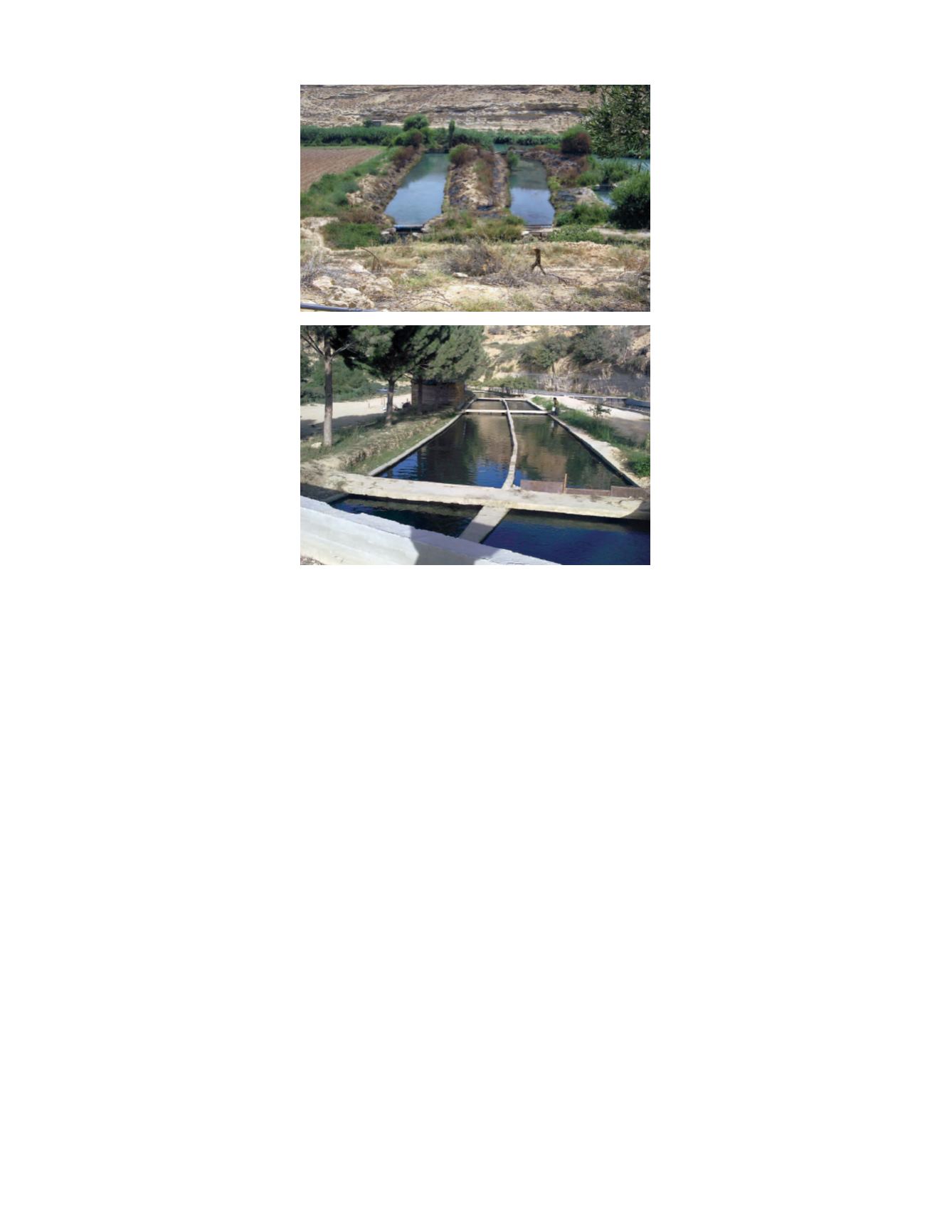

Raceway Design and

Construction

The design and construction

of ponds and raceways on fish farms

of the Assi River valley is diverse.

Only earthen raceways (Fig. 4) are

used by 43 percent of farmers, both

earthen and concrete raceways

are used by 34 percent and only

concrete raceways (Fig. 5) are used

by 23 percent. In general, those with

concrete raceways thought they

were better and those with earthen

raceways defended their use.

There are two main reasons to

explain the prevalence of earthen

raceways along the Assi River.

First, earthen raceways are less

expensive to build than concrete

raceways. Trout farmers who

believe that concrete raceways

are better often lack the funds to

transform their earthen raceways

to concrete. Some trout farmers

who rent raceways perceive the

expense of transforming earthen

raceways to concrete raceways as

unnecessary, inasmuch as they

will not benefit from the investment

over time because they do not own them.

The other reason to explain the prevalence of earthen raceways

is that many farmers assert that trout reared in earthen raceways are

healthier, more colorful and a better-quality product. Thirty-eight

percent of farmers believe that earthen raceways are better for trout

health and welfare than concrete raceways. Some of the reasons given

were that fish feed on small plants growing in the soil and hence

obtain more nutrients and grow faster. Also, some believe the soil acts

as a filter, cleaning the water in which trout are grown.

A majority (53 percent) of trout farmers thought yields from

earthen raceways were better than from concrete raceways. Another 13

percent believe that rearing rainbow trout in earthen or concrete race-

ways gives similar results and therefore deem the additional expense

of building a concrete raceway unnecessary. Piper

et al

. (1982) also

reported that some trout farmers stand by their opinion with respect to

high yields from earthen raceways. Survival of rainbow trout does not

seem to depend on the type of the raceway, earthen or concrete.

Thirty four percent believed that concrete tanks were better

because, in contrast to earthen tanks, they can be totally cleaned of

waste. Furthermore, no aquatic animal can dig into them and allow

fish to escape. They are difficult for pests or predators (e.g. snakes,

rats or frogs) to enter and prey upon trout fingerlings. Eleven percent

of farmers stated that they were certain that concrete raceways helped

reduce fingerling mortality and offered better population control. Fish

and water quality in concrete raceways are much easier to manage

than in earthen raceways (Piper

et al

. 1982, Hinshaw 2000, Dunning

and Sloan 2001).

( C O N T I N U E D O N P A G E 2 0 )

TOP, FIGURE 4.

Earthen raceways along the Assi River, Lebanon.

BOTTOM, FIGURE 5.

Concrete raceways along the Assi River, Lebanon.